The younger grades, the kindergartners, first and second graders I discovered were relatively easy to keep occupied and engaged, but somewhat more difficult to maintain any sort of order, so I eventually gave up. In time, I resigned myself to the path of least resistance--scatter a few balls and other items around the gym floor, open the doors, and get out of the way. The next twenty-five minutes was a healthy mixture of screaming, running around in circles and general chaos.

The upper grades, third through sixth grades, took meticulous planning and constant revision throughout each activity. Common phrases that I heard repeatedly throughout different games included: "That isn't fair," "She stepped on the line," "He touched the ball last," "Those two can't be on the same team," and more than a few times, crying.

With the younger grades, it was twenty-five minutes of play, an opportunity to run, jump, spin, bounce, dance, wiggle, all without restraint from any authority figure. For the upper grades, it became a practice in equity and fairness, of rules and regulations, a system that needed structure and guidelines with black and white statutes that could be easily identified and understood.

It was exhausting.

What I discovered from this experience, is that developmentally, the early adolescent years is when children become very concerned with a world of rules and fairness. While still rudimentary, it was very clear that the idea of thing being "fair" was paramount. As their awareness of the world around them developed, along with it came the need for comparison with others, competition, and a keen insight into the hierarchy of power and justice.

I'm just not sure if this need for fairness was about being fair, or about not being on the losing side, as the complaints usually came from the team that was weaker, or the individual that would benefit the most from the absolute fidelity to whichever rule was in play. In fact, many times, the desire for something to be fair was overlooked if it was advantageous to an individual, and not noticed by the whole. So, I do not think that it was necessarily about the righteous nature of the rules, or the need for equity, it was about establishing a system that could be taken advantage of when needed in order to further one's owns goals.

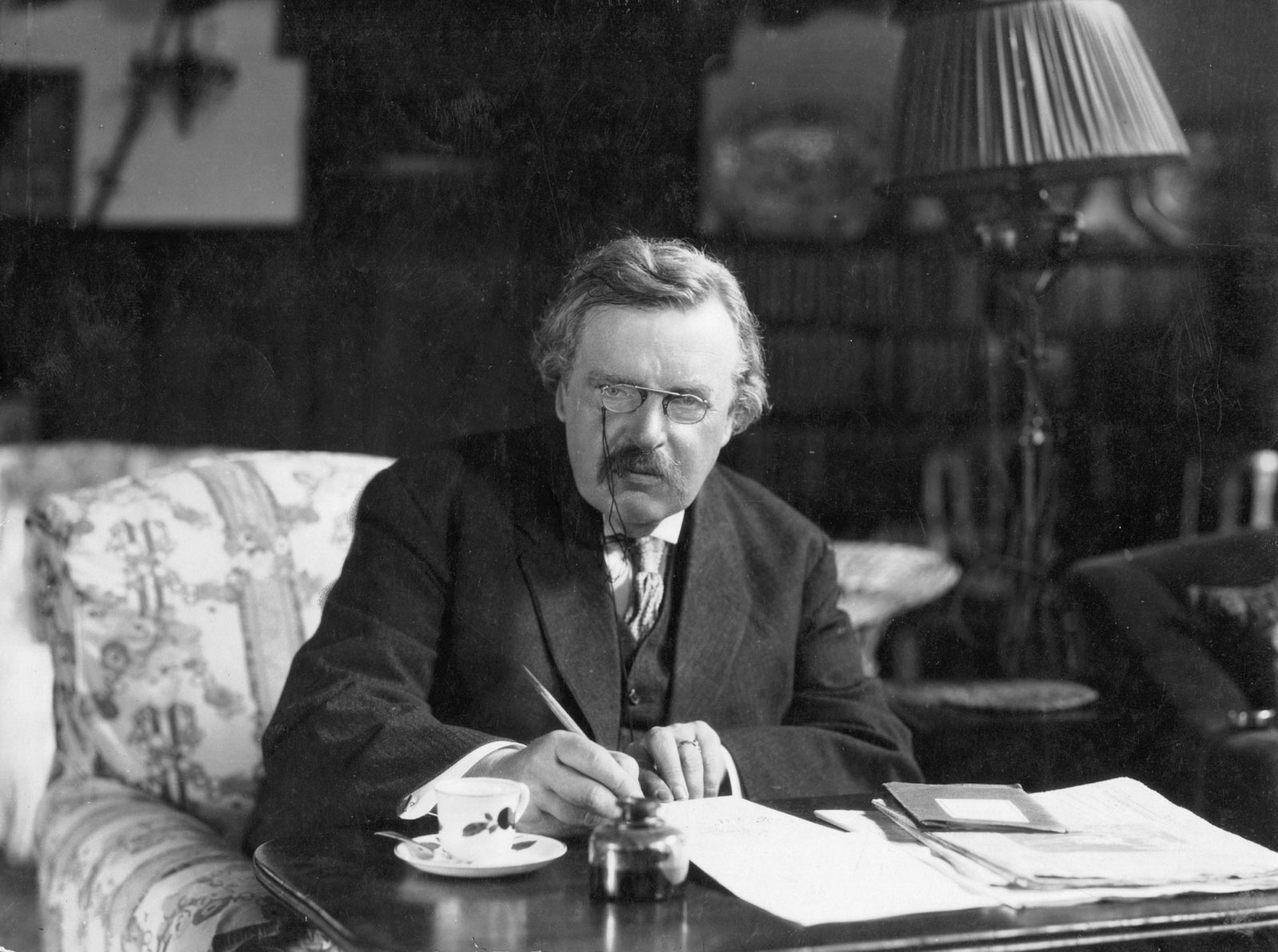

In On Household God's and Goblins, G.K. Chesterton writes, "For children are innocent and love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy." This growth from childhood to adulthood is often marked with a transition from a world view that is purely black and white, good and evil, or right and wrong, to a world view that consists of several shades of gray, levels of righteousness, and a spectrum of morality that is constantly in fluctuation and often subject to relative circumstances or scenarios.

This is not uncommon at any age, but the games become much more complex and usually entail higher stakes. A driver who complains about getting pulled over and remarks "it's not fair, other people were speeding too" is also likely to wish for a driver that speeds past them the following day to be ticketed. It is easy to justify a desire for someone else to get caught and face the consequences of their actions in the name of justice, yet difficult not to rationalize and make excuses for ourselves when we are the ones breaking the rules. What is worse, is when we create something pernicious masked as something virtuous.

This ability to advocate for an action or process which for one reason, but under the guise of another is a dangerous process of thinking. In its most harmless form, it allows a person to acquire personal gain with the appearance of helping another. When we were kids, my parents would tell us that our ice cream cones were dripping and the only way to prevent that was for them to eat a portion of it to prevent it from making a mess. At it's most malicious, it can carry out ruthless practices which are protected by the shroud of morality. Extreme examples include Jim Crow Laws and the Law for Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases.

I wonder if we are always honest with ourselves when it comes to our own motivations, or if we are sometimes so frightened by our own selfishness or ill intent that we must masquerade them as something upright and righteous? Are we at times so painfully aware that the blatant nature of our own avarice or malice will be so repugnant to another person that we plead its merit based on a shroud of ethical priority? Sometimes, sound reasoning can be the best disguise for ill intentions, even from the person who is creating them.

Human beings are complex creatures capable of a wide variety of actions, based on a wide variety of values and paradigms of thoughts, some of which are obscured even to the mind of the person behind the actions. We just need to make sure that we actually think what we believe.

As a scientist, your main points scream, "Survival of the fittest!" It makes some sense to me that at the 4-6th grade level is this mental shift towards "fairness" as this is the time parents start to "wean" their children from constant protection. We are less likely to rush to their aid when they stumble and wait to see how they endure conflict with their peers before stepping in as a means of guiding them toward independence. This phenomenon of fitting fairness to your advantage is humanity's way of reasoning it's way out of being the weakest link.

ReplyDeleteIn my experience, those who have the greatest weaknesses are those who are the best at finding "masks of fairness" to hide their selfish decision making. For many, I think masking these weaknesses is the path of least resistance, when the only alternative is to work to improve. Dangerous, indeed.It's easier to make an excuse, than to put in the work. To blame another group for your inadequacies.

It seems those who openly admit to their faults are often those who choose to work to improve or adjust to compensate. -Allison